America, Can You Hear Them now?

By A. C. |

At times, there’s an insatiable effort to neutralize the spirit of people. It’s cruel to ask someone to be less them, and consequently become more of something else. In Women Native, Other, philosopher Trinh T. Minh Ha states that “it’s a positivist dream of a neutralized language that strips off all its singularity to become nature’s exact, unmisted reflection” (24). In a specific sense, the Negro spirituals were blacks’ way of expressing and declaring their identity. As religious-based songs developed by the black Christian slaves in the South, the spirituals have become a perpetual language for black Christians. With hearts drenched in suffering, they allowed their aching souls to be lulled through song.

With the enslavement of blacks in the Americas, an attempt was made to dwindle their existence down to a minuscule socially-constructed state of nature, which was imposed on them by the salivating capitalist and plantation owner. In this grotesque effort to diminish the existence of human beings, Southern slave owners enabled the blacks to create an existence for themselves. And in a failed oppression, blacks have allowed their language to be one that can only be understood by the community they survive in. Their pain and woe have been sent down the infinite well of generations, and their children are laurelled with their triumphant sorrows. You can execute people, oppress them, and have control over their actions or minds, but what is impossible is the unfathomable act of silencing one’s soul. The soul is sublime, and we can hear the majestic quality of it in the Negro spiritual.

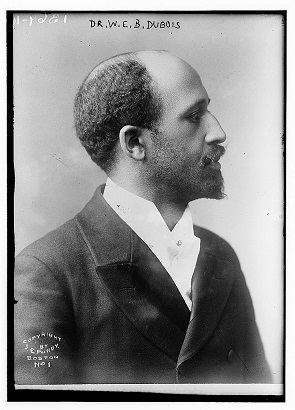

Profile of W. E. B. DuBois

My adoration for, as W.E.B Du Bois puts it phenomenally, The Souls of Black Folk, is the refusal to forget or relinquish the beauty developed from the agony endured during slavery. “Little of beauty has American given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom,” wrote Du Bois in 1903. “[T]he human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic expression of the slave—stands today not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.” Du Bois is asserting that the spirituals are without a doubt the definitive element in expressing loveliness through the pain the slaves endured. It is the history of the slave, and their offering of art and grace from suffering, from enduring something so indescribably inhuman.

In part, I visited Canaan Baptist Church of Christ (est. 1932) simply to hear a gospel choir. But also, in hope to be inspired by the perpetuity of the Negro spirituals. It’s strange how you can visit a place countless times and blur out its surroundings. Amy Ruth’s in Harlem is one of my favorite restaurants. I’ve consumed large-portioned soul food meals there with family, friends, bad dates, good ones, and by my lonesome. Never have I noticed Canaan Baptist Church across the street. The church has an ominous feel to it. On the line, waiting to get in – there’s a gargantuan number of tourists. It’s an attraction: it seems to have transformed from one thing to another. A long time ago the church’s congregants were migrants from the South. Today, without the tourists, the church would be hollow. The church made me feel like a visitor, and as welcoming as this is, I felt like the church would soon become a memory.

Canaan, with its pale awning and gloomy aesthetic looks like an abandoned movie theater; it’s a place easily missed while strolling along a Harlem sidewalk. But it’s there, and its history, the soul of the place, a priceless one, is one I won’t forget. Upon entering and seeing its red interior, creating a passionate feel, I knew I was going to experience something. Women marching to the beat of their outfits (hats decorated creating a nostalgia of being a child in arts and crafts), foreigners flocking in with their film fully stocked, holding their ferocious cameras (all appearing just confused, as enthused as the others), and worshipers. Everyone sat down, fidgeting in their seats as if waiting to get results from a test or doctor, waiting for something. The collection plate was passed around right after the choir finished singing. It seemed like people left often after hearing their voices. But no one left. Everyone stood for the service. I thought I would leave but I couldn’t find the will to get up. I was taken aback by the choir, that their voices sort of pinned me to my seat and kept me resting there till I was ready to continue forth with my day. Resting in Canaan Baptist Church are the souls of people who haven’t been seen by anyone but their God. And what was so abundantly clear was how a form of oppression can make the heart of the people. It was so clear that not only was I unable to look away but I didn’t want to.

In Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, his concept of double-consciousness, possibly his most referred-to concept, can be correlated with the profoundness of the Negro spiritual. To be doubly conscious is to exist in conflicting, or juxtaposing identities. You have the national identity, which can be viewed as the whites’ dogma, and an ethnic cultural identity, which can play the role of a subservient one. According to Du Bois, the veil only exists for blacks since they were targeted and made to feel alienated in their nation. The Negro spirituals—the gospel—is blacks’ commitment to establishing their distinctiveness as well as the imperative deed of creating their historical narrative and resisting subjection. Blacks have developed a way to rise out of this imposed subordination and create something that describes the true nature of their beings: strong, unrelenting, loved by God, and as beautiful as anything else in America. Du Bois comments on this lasting narrative stating, “The child sang it to his children and they to their children’s children, and so two hundred years it has travelled down to us and we sing it to our children, knowing as little as our fathers what its words may mean, but knowing well the meaning of its music.” Their truth is through passion-filled musical notes of mourning, and it is passed down from generation to generation, it is the historical lesson for the black children of America.

Du Bois writes that the sorrow songs, his evocative name for the Negro spirituals, allowed a freedom for the black slaves. Withdrawing the ability for someone to judge you heinously and with discrimination is undoubtedly the act of wielding a power that can do nothing but strengthen a spirit. This translation of gloom into vibrant energy is felt through song. At Canaan, the singing is jarring. It’s indescribable. It’s like when you think you’ve heard certain words before but something about them being expressed in song blurs the meaning of the words and gives them an ephemerally spiritual quality. Words don’t mean things on their own; we attach meanings to them. And at Canaan, the simple and poignant repetition of certain phrases such as “God is in me” is very powerful to the ear. The language that exists in the gospel is one that can only exist when its words have lived a certain truth. And it seems like the spiritual serves more than as a form of entertainment, because as lovely as it may appear, it’s also devastating that it had to be created.