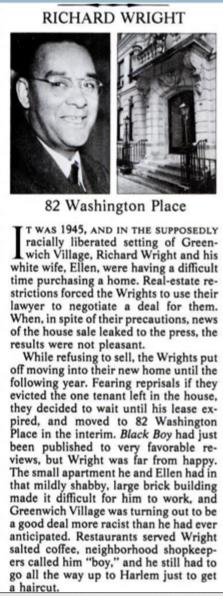

A Mississippi Man With New York Aspirations: Richard Wright in Greenwich Village

By C. A. |

Standing between a luxury building and short narrow townhouses, 82 Washington Place seems almost out of place amid these structures and with the NYU freshmen dorms rounding out the other corner. But that’s the beauty of New York City. Streets filled with all types of buildings and housing their own history within them. This six-story building is the only one of its kind on the block with the fire escapes facing you as you walk up to it, street lamps illuminating the stairs at night, and massively heavy ten foot tall glass doors. As you look up from the white stone that wraps around the first two floors, you see the third floor turn into a traditional red-layered brick façade that has aged over time creating a checkered effect of red and black. The first-floor windowsills are decorated with vibrant potted plants, which the tenants replace with wreaths during the holidays, creating a welcoming environment. 82 Washington Place is more, however, than just a comfortable residence in one of Manhattan’s priciest neighborhoods. It is also a sanctioned literary landmark where no less than three famous American authors—Richard Wright, Willa Cather, and James Baldwin—made their home.

Richard Wright wrote his autobiographical novel, Black Boy, while living at this address. The novel tell Wright’s story as a young black boy from Mississippi and his troubles and tribulations. It is during his childhood in the South that he begins to understand and witness first-hand the racial disparity that comes with being black in a white person’s world. However, it isn’t just the undeniable truth about race that creates a hostile Wright, but a “strong impression of life in a virtually loveless family.” The critic Joseph Skerrett continues, “Particularly conspicuous by its absence is the memory of paternal love and affection; even before his abandonment of his family, when Richard was about four years old, Nathaniel Wright seems to have cast only an emotionally pale shadow in his son’s direction.” (Skerrett 84) This fact is particularly important to understand not only Wright’s rebellious nature, but also his motives, as the young Wright never truly has the support and love of his family and is constantly berated with authoritative oppression within his own family dynamic. Coupled with the racial limitations of being black, this family dynamic leads to unhappiness and unrest. Wright is constantly oppressed intellectually, which is reflected in the novel when an employer of his scoffs at the idea of him becoming a writer. Heading north for intellectual and personal salvation, Wright begins to grow into his own as he makes his way to Chicago chasing after a fuller life and the desire to live it freely. Aspiring to write from a young age, Wright joined the Federal Writers’ Project in 1937.

Richard Wright wrote his autobiographical novel, Black Boy, while living at this address. The novel tell Wright’s story as a young black boy from Mississippi and his troubles and tribulations. It is during his childhood in the South that he begins to understand and witness first-hand the racial disparity that comes with being black in a white person’s world. However, it isn’t just the undeniable truth about race that creates a hostile Wright, but a “strong impression of life in a virtually loveless family.” The critic Joseph Skerrett continues, “Particularly conspicuous by its absence is the memory of paternal love and affection; even before his abandonment of his family, when Richard was about four years old, Nathaniel Wright seems to have cast only an emotionally pale shadow in his son’s direction.” (Skerrett 84) This fact is particularly important to understand not only Wright’s rebellious nature, but also his motives, as the young Wright never truly has the support and love of his family and is constantly berated with authoritative oppression within his own family dynamic. Coupled with the racial limitations of being black, this family dynamic leads to unhappiness and unrest. Wright is constantly oppressed intellectually, which is reflected in the novel when an employer of his scoffs at the idea of him becoming a writer. Heading north for intellectual and personal salvation, Wright begins to grow into his own as he makes his way to Chicago chasing after a fuller life and the desire to live it freely. Aspiring to write from a young age, Wright joined the Federal Writers’ Project in 1937.

In 1945, he moved to New York City for a better chance to get published. Wright had complicated feelings about the Eastern city, once telling Ralph Ellison, during an absence, that he was “itching for the poisoned life of NY again.” Wright and his wife managed to move from Brooklyn to Greenwich Village and, “through friends they were able to move into a third-floor apartment in a beaux arts turn-of-the-century apartment building, a block away from Washington Square. For a racially mixed couple, it was a breakthrough” (Rowley 321). Much like New York City, where Black Boy was published in 1945, Wright considered himself to be a walking contradiction: “A Negro married to a white girl, a communist who cannot stand being a member of the Communist group, a writer who does not and cannot and will not write as other writers write.”(Rowley 320). This was of course before the Civil Rights Movement began, and for a writer of Wright’s considerable talent, the West Village was the epicenter of New York for artistic bohemians.

82 Washington Place was at the center of the artistic world of Greenwich Village for talented individuals such as Wright during the early to mid twentieth century, but now it stands as a home for those young and old, people looking to start their lives or simply to enjoy their retirement. Having been raised in this building and having watched the neighborhood and tenants evolve over the years, I can’t help but realize that, as the surrounding buildings grow taller and newer, this building remains the same. Yet growth still happens inside these walls: the very same growth Wright sought in the writing he did here, and the very same growth I’ve enjoyed for the past twenty-five years, and which led me, eventually, to become an English major myself.

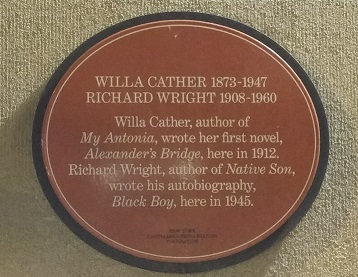

Commemorative plaque inside 82 Washington Place

Works Cited

Rowley, Hazel. Richard Wright: The Life and Times. New York: Henry Holt, 2001. Print.

Skerrett, Joseph T.. “Richard Wright, Writing and Identity”. Callaloo 7 (1979): 84–94. Web…

Smith, Sidonie Ann. “Richard Wright’s “black Boy”: The Creative Impulse as Rebellion”. The Southern Literary Journal 5.1 (1972): 123–136. Web…

Hopkins, Ellen. “Where They lived.” New York Magazine. March 7, 1983. 43. Web.

1 Comment

Angela Tribue

July 3, 2023Wonderful!